What Does Your Future Hold? The power of curiosity in a changing and divided world

By: Nieset LeFevre

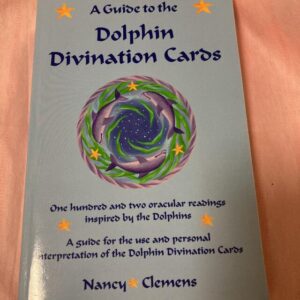

It was the seventeenth of June and seven sleepy and delirious WRFI students sat around Jean Wallace’s sturdy wood table stacked with cookies and homemade spice bars. Full and content after our first 50-mile day we decided the logical thing to do at 10:30 PM, when we should be sleeping, is to conduct a reading from a bowl brimming with enchanting dolphin-covered tarot cards.

As we reached in and focused all of our best intentions and energy through the end of our fingertips to pull the most meaningful cards, I couldn’t help but think how opportunities like Cycle the Rockies are so unique. There is a healthy amount of fear that goes into signing up for a course where semi-trucks will be whizzing by you going 70 miles per hour. What counteracts that fear is the collective goal of safety and the group incentive to be curious and learn from those who have different experiences than you. We are all working on finding more ways to be hopeful and our individual curiosity builds a collective bridge between oneself and the unknown. I think it is better to have diverse groups of people, like those I’ve met on this course, to cross that bridge with you.

According to my tarot, right now I am in a state called a “deep dive,” which I think is appropriate considering the adventure each of us on this trip have all decided to go on; but my future is what struck me the most. As I flipped over my last rounded dolphin card the word “curiosity” appeared before my eyes, and I think that is a very, very good sign. Let me explain how fear and curiosity have evolved for me beyond my own personal experience during Cycle the Rockies.

Just outside of Martinsdale, MT alongside the Musselshell River we sat in a naturally lit dining room where generations of Shane Moe’s family have lived. From Moe we learned that many ranchers in the area have had to sell cattle to avoid bankruptcy from drought, non-native grass encroachment and other factors such as fluctuations in cattle and fuel prices making it harder and harder to be profitable. In recent years, Moe has decided to take to regenerative practices on his land, in part because “necessity pushed me to do the right thing,” but also because of his love for the land and interest in new ways of ranching.

As we all ate a lunch of smooshed white tortillas stuffed with anything we could find in our panniers, Moe explained his journey from revitalizing his bare soil with vermicast, a strange but effective way of using worm dung to add nutrients to the soil, to rotating his cattle more frequently for optimal grazing, and using a chicken tractor to add nutrients to the soil and increase the quality of meat.

It turns out, changing your way of life to support novel practices comes with a great deal of risk, but also high reward. Moe is seeing positive results in his crop health and availability for his cattle sooner than he was expecting. This is a similar tale to what Steve Charter, another regenerative Montanan rancher, told us as well.

What these ranchers seem to be realizing is that “normal” ways of living off of the land are not going to work long-term, neither economically nor environmentally. Moe and Charter are two of a small demographic of agriculturalists who have had the courage to overcome and continue to work through the initial fear and risk that comes with changing conventional ranching.

On a larger scale than ranching, I have noticed risk as a significant deterrent not only from regenerative practices but also from energy transformation and climate adaptation in general. Not because risk is inherently bad (our entrepreneurial economy relies on people taking risks), but due to the associated fear that contributes to cases such as climate denialism. The way I see it, deeply rooted in climate denial lies an inherent fear of accepting the consequences of our anthropomorphic actions. It is scary to think that the way you live your life is going to be threatened by moving away from the fossil fuel industry, for example. Furthermore, accepting climate change as a human-caused issue gives responsibility to all humans which is a lot of weight to carry. However, the more we distribute it, the lighter the load will feel. In the words of Montana writer and co-founder of AERO, Elizabeth Wood, “People don’t behave badly because they want to, they behave badly because they are frightened on some level.” I believe this helps interpret a large demographic of climate deniers present today.

The climate crisis raises an interesting conundrum for ranchers, but also for all of us. Which is riskier: doing what is comfortable but clearly unsustainable, or reconfiguring what you know, ideally before necessity chooses for you? I would like to propose the idea that doing the “ordinary” can be more dangerous than we recognize, and perhaps sustainable practices are not all that risky — they are just fear-invoking because they are novel.

So what do Shane Moe and Steve Charter have in common? While Charter and Moe are courageous in their lifestyles, they also maintain a healthy dose of curiosity. Curiosity helps to incentivise tough conversations and can be used as an instrument to break barriers that seem impossible to overcome. Being on a month-long bike tour where there is nothing but open road and endless time to sit and spin the pedals has challenged me to stretch my mind in new ways. After pedaling about 660 miles to merge my personal and societal observations, I’ve come to the conclusion that if fear hinders action to mitigate and adapt to climate change, then we must use curiosity must spark it.