Our second day in the backcountry was our first day hiking in the bottom of Horseshoe Canyon. Within the first hour of our trek, Ben stopped in his tracks and stooped to grab something half buried in the sand. Amid a mosaic of stones and pebbles, the shiny red glint of a small specimen had caught his eye. It was a flat triangular thing, maybe an inch from base to tip, and it had clearly not achieved this form through the forces of nature. All eight of us crowded around for a show and tell that would spark a whole new topic of intrigue in canyon country. “It’s the tip of an arrowhead! Ancient people made them out of chert,” Ben informed us. He pointed to the once razor sharp edges and drew our attention to scalloped ridges indicative of human handiwork. We passed the artifact around and each took a turn imagining the prehistoric person who had created it. At this point, we realized that frequently scanning the ground was just as important as gaping at the immense beauty of the canyon surrounding us.

Our second day in the backcountry was our first day hiking in the bottom of Horseshoe Canyon. Within the first hour of our trek, Ben stopped in his tracks and stooped to grab something half buried in the sand. Amid a mosaic of stones and pebbles, the shiny red glint of a small specimen had caught his eye. It was a flat triangular thing, maybe an inch from base to tip, and it had clearly not achieved this form through the forces of nature. All eight of us crowded around for a show and tell that would spark a whole new topic of intrigue in canyon country. “It’s the tip of an arrowhead! Ancient people made them out of chert,” Ben informed us. He pointed to the once razor sharp edges and drew our attention to scalloped ridges indicative of human handiwork. We passed the artifact around and each took a turn imagining the prehistoric person who had created it. At this point, we realized that frequently scanning the ground was just as important as gaping at the immense beauty of the canyon surrounding us.

During this first section of our course, we read Singing Stone by Tom Flieschner. At the end of this book, he asks, “How do we live here? How should we live here?” in reference to the high deserts of the Colorado Plateau. Initially, I thought that maybe we shouldn’t live here. Maybe the delicate soils of the desert can’t tolerate our impacts. Perhaps the water sources in this region are too scant to support any sort of human population. But people lived here before. They lived here for thousands of years! The Colorado Plateau harbors a great deal of evidence that the Ancestral Puebloans and the Fremont people utilized an intimate knowledge of the land to support their civilizations.

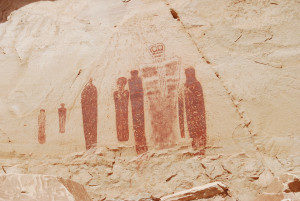

Our next encounter with the area’s past inhabitants occurred on the fifth day of our journey down Horseshoe Canyon. We entered an area that has been incorporated as a satellite unit of Canyonlands National Park. Not long after passing into this new territory, we came across a large alcove. The walls of this sandstone overhang were covered with dark red paintings of long-bodied humanoid shapes with short little limbs. Some had horns, some held spear-like objects, but my favorites were those that had intricate patterns of zig-zags and animal figures covering the interior of their bodies. One that caught my attention in particular had two goats on either side of its chest.

There is no way of knowing what message, if any, the artists of these pictographs were trying to convey, but it is always fun to speculate. Perhaps the goat-covered man was symbolic of the connection people had to goats as a source of food. There was another image that was a horizontal oval with small vertical hash marks attached to its bottom side. They then continued down the wall for about a foot. I supposed that it was a rain cloud , and that this panel praised the rainwater necessary for the crops these people grew. Maybe the intention of these painting was to tell the tales of how to live within the means supplied by this landscape.

On the fourth morning of our trip along the Dirty Devil River, we had class in No Man’s Canyon. As we wrapped up our session for the day, Katie pointed out a rather large alcove in the canyon wall. The eight of us wandered over to check out a pile of strategically placed flat rocks held together by some sort of cement, the remnants of an ancient structure.

The alcove was high above us and we were unable to scramble up to it, so we were unable confirm its purpose, but it was likely a dwelling or a place for storing food. At the foot of this aged structure, we spent some time thinking about what life was like for these people. I reflected on how they might have interacted within their families and within their communities. I imagined a father taking his son for a walk to find perfect pieces of chert for making tools. He would spend hours teaching his child the tedious process of chipping away tiny pieces of the red stones in just the right way. During one instructional session, a neighbor may have come over to ask the father for help with building a new grainery, as the corn he had planted was doing very well that year. I imagined that these people were close to the land, their livelihood depended on it, so they taught each other to be very intentional, to take great care in the things they did.

A couple days later, we were hiking up Larry Canyon. We followed a creek bed, the sides of which were eight-foot high vertical walls of dirt. Horizontal lines of sand, decomposed organic matter, and pebbles told us the history of the movement of sediment and water through the canyon. Amid the layers of strata, we saw a bubble of charcoal and ash. We were lucky enough to have stumbled upon a prehistoric fire ring! I approached the dark oval, which was set about a foot below eye level. The top of the terrace it was embedded in was several feet above my head. It takes a very long time for an inch of new soil to form in this dry climate, so the layers of sand and pebbles I looked up at served as a perfect visual for the 800 years that have passed since this fire ring was used.

The desert is a place where I have experienced profound silence, unlike that I have known anywhere else. There are times when no breeze rustles through the trees, no flowing water babbles, and no creatures chitter. Have these moments always existed here? Has this landscape changed in the last 800 years? How will the things we leave behind affect the landscape 800 years in the future? I like to think that the ancient people of this region did have these silences, and used them as a reminder that life-giving resources are not in abundance, but rather, can be carefully reaped to support civilization. I like to think that we can contemplate the lessons of the past and interpret these silences in the same way.

One Reply to “Katie Atherly: Lessons from Ruins and Silences”

Comments are closed.

Hi Katie (et al), It has been wonderful to read your experiences and thoughts in the canyons, thanks for writing with great attention and care. I can picture and remember all the places you mention, and I truly miss being there this year. Hope the course finishes up well for you all, and I look forward to hearing more about your experiences and conclusions from a season in the field. – Dave Morris