My heart heavy, my mind intrigued, and my body attentive, I listened to Hal Herring tell a tale of America’s public lands. Details left and right—the Homestead Act, droughts, Dust Bowl, Great Depression, Clean Water Act—he built a narrative of the rise of America’s public lands but never left out the dark truth of America’s stolen land. Unlike a high school textbook, the genocide of Native Americans and their cultures is as much a part of this tale as the acts and events that followed. When Hal spoke, his eyes were full of passion. He is a teller of this story out of a sense of duty, determined to bring America’s broken history to light.

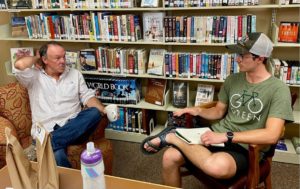

It was Day 18 of the Cycle the Rockies course. We were off our bikes for a day in Augusta, Montana, making frequent visits to the general store and coffee shops and having class meetings at the public library. We’d arrived the day prior, riding 44 miles of long rolling hills through the prairie, and we welcomed a rest day.

What Hal described came as no surprise to me; we’d been discussing Native American issues for some time. Still, what he said brought me to that uncomfortable place—doubting my perspective and credibility as a white man in conversations about race and historical injustice in a place forcibly taken by earlier white men.

“Americans are the best at destruction in the history of mankind…” Hal didn’t pull punches. After the U.S. Cavalry killed or forcibly relocated most Native Americans in the West, white men were encouraged to go West and take something for nothing. Manifest Destiny. The Homestead Act.

It is my understanding that my ancestors were not in the States at this time in history, but as a white male I still felt uncomfortable being a part of that narrative.

“… the best at destruction… but also the best at restoration.” Hal revealed a beam of hope. Americans noticed that their methods of grazing sheep and cutting down forests was causing devastating watersheds and ruining the land. The Clean Water Act. National Forest land.

Since that day, we’ve talked extensively about what we now do in this land and have met with several people doing good things. We spent some days on the Blackfeet Reservation and talked with people about climate change, traditional ecological knowledge and Native American perspectives. I’ve come to better understand what Hal had to say that day.

“I cannot change history,” he said, “…the onus is on the white man to make sure the Native voices can be heard.” I understand that I have white privilege and benefit from the crimes of history, but my actions are a product of my time and my beliefs—I am not purely a product of the past. I want to help change the world for the better, even if I’m still trying to figure out how I can best do that.

My current interests are in climate change and energy and many solutions to these problems are equitable and positive for people and the environment. In East Glacier we met with Loren Bird Rattler, an agriculture expert of the Blackfeet Nation and an instructor at Montana State University. He is doing a lot of agricultural work on the reservation. One project involves a bison—and cattle—processing facility on the reservation that would focus on grass-fed animals. It would reduce carbon emissions, promote economic growth on and around the reservation, and provide local ranchers a place to send grass-fed cattle without mixing their meat with corn-fed meat. Loren described a vast system of change he’s working on and the solutions it presents for a range of problems.

Loren also works with AmeriCorps to get people involved with land and community involvement on the reservation, something I could see myself becoming a part of.

The world is worth taking care of, no matter its history. Preserving the land we use transcends us. Helen Augare of the Blackfeet Nation described Native Americans’ relationship with these lands. It’s not about ownership, the way non-Native Americans typically view it. Rather, they would accept the land’s resources as gifts, take what is needed, and care for and defend its health and beauty. I find this relationship to be wonderful and a key idea in climate solutions. For too long, industrial society has taken too much without returning the favor to the land and everyone is suffering the consequences.

Hal Herring believes deeply in the conservation about our natural land and resources. It doesn’t even have to be about climate change. “Is it a valuable thing to be so affronted by things being destroyed?” he asked us in a rhetorical sense, to take and ponder. After everyone I’ve met on this trip and lives I’ve witnessed, I believe it is a valuable thing to care deeply about things being destroyed. I want to see these lands being taken care of in a way that’s healthy for the earth and the people of these communities. I’ve found that there are many avenues of engagement for people like me to become involved in building solutions. There are opportunities to learn more about the land and communities that are creating positive, equitable solutions to climate change.

Learning more about my place in these issues and about what other people do to make the world better, I feel better prepared to handle the uncomfortable place I find myself. I can’t change history, but I can do everything in my power to make a better future for everyone else. That matters.

Silas Andrews is from Great Falls, MT and currently pursuing a bachelor’s degree in physics at Montana State University.